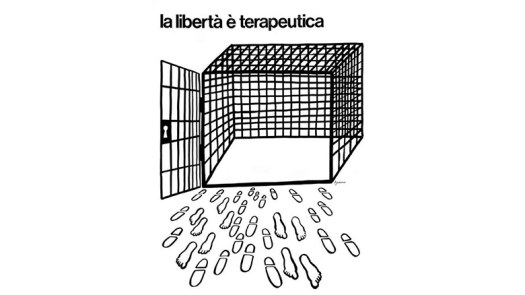

La psychiatrie en France, zone de non-droit (par Pink Belette)

Une patiente française sous contrainte fait son « audit » dans le cadre de la campagne pour soutenir l’Abolition totale des soins et de l’hospitalisation sans consentement en application de la CDPH de l’ONU

http://depsychiatriser.blogspot.no/2016/03/la-psychiatrie-en-france-zone-de-non.html

Pourquoi je suis contre les « soins sous contrainte » :

On pourrait croire que, au pays de la liberté, on a encore droit à son intégrité morale et physique.

Rien n’est plus faux. Par experience, impossible pour quiconque d’échapper à un soin sous contrainte (SPDT, « soin à la demande d’un tiers » ou « péril imminent »).

Il suffit que : une personne la demande (que ce soit la famille, un voisin…), qu’on soit « pas bien », déstabilisé, agité, « instable », en colère, dépressif, sur la défensive, « en opposition », « délirant », amaigri, boulimique, fumeur de shit, drogué…

Il suffit aussi qu’on refuse l’hospitalisation ou un traitement pour que les médecins se relaient pour demander un soin sous contrainte. Une fois hospitalisé, « on » vous fait comprendre que vous perdez vos droits à la personne, l’argument étant : « maintenant on est responsable de vous pour TOUT »… Par contre, vis-à-vis de vous, « on » n’est responsable de rien…

Depuis la loi Bachelot du 5 Juillet 2011, en particulier si on a le malheur de contester le diagnostic ou le traitement, c’est alors après la sortie d’hospitalisation qu’on ne peut plus se débarrasser de la contrainte, et c’est là que c’est le plus pervers : injections forcées, consultations obligatoires avec un praticien hospitalier non choisi (à la rigueur, on a le choix entre deux médecins).

Le pire : si on refuse de se rendre au centre médico-psychologique du secteur assigné, la police vient gentiment vous cueillir chez vous pour vous hospitaliser en soins obligatoires à un degré encore plus coercitif (SPDRE, « sur la demande de l’Etat ») et sur un temps plus long et sans contact autorisé avec l’extérieur (!) jusqu’à ce qu’il aient réussi à réduire votre volonté à néant. Ainsi, il arrive que les personnes concernées doivent abandonner leur logement pour « vivre » en psychiatrie (parfois pendant des dizaines d’années, voir le cas de Dimitri Fargette)…

Je suis témoin : en France, il y a réellement du souci à se faire…

- Il n’y a aucune alternative à la psychiatrie institutionnelle (lobbying des psychiatres ET de l’industrie pharmaceutique contre d’autres formes de thérapies) ;

- Aucune littérature ou culture antipsychiatrique (des « survivants », il n’y en a pas…)

- L’Ordre des Medecins Psychiatres qui suspend : tout psychiatre « en décalage » avec le système consensuel (d’après le Dr. O.G, psychiatre libéral et ex-chef de clinique) ;

- L’Ordre des Medecins Psychiatres qui suspend : un psychiatre responsable de la mort d’une patiente… seulement pour 2 semaines (voir l’affaire Florence Edaine)

- La « Mafia des tutelles » : tout patient faisant des séjours répétés est automatiquement placé sous curatelle ou tutelle (sans consentement, c’est renforcé)…

- Des mères se voient enlever leurs enfants immédiatement après la pose d’un diagnostic de maladie mentale ; jamais de scandale médiatique…

- On fait comprendre aux femmes en âge de procréer qu’il faut surtout adopter la contraception, en sous-entendant qu’on leur enlèverait leur enfant de toute façon. Ce qu’on ne leur dit pas, c’est que tous les neuroleptiques passent la barrière placentaire, c’est pourquoi j’ai entendu parler d’autant de cas d’avortements spontanés chez les femmes sous traitement. Dixit une infirmière, on donne de l’Haldol aux femmes enceintes, ce qui « prouverait » soi-disant « le peu de nocivité de l’Haldol » (!). Jamais d’étude là-dessus ni de scandale médiatique…

- Des services fermés qui regorgent de dépressifs qui ne sont pas en « péril imminent » et qui se sentent surtout mal de recevoir par exemple 4(!) antidépresseurs à la fois…

- Une cellule d’isolement toujours occupée (appelée « chambre de soins intensifs »!), ce qui participe du « folklore »…

- « Abonné une fois, abonné toujours » : les traitements qu’on ne peut plus JAMAIS arrêter ;

- Aucune étude à long-terme sur les effets des psychotropes…

- Aucun recours en cas d’abus psychiatriques (système interne de « médiation » caduc : mal vous en prend d’écrire une lettre au directeur de l’établissement…)

Pourquoi je suis contre ce nouveau système de « Juge des Libertés et Détentions » (relatif à la loi du 27 septembre 2013) :

On vous fait croire que c’est une voie de recours. Rien n’est plus faux, à part en cas de vice de forme (ce qui n’arrive quasiment jamais, puisque les psychiatres ont intérêt à ce que la procédure se passe en bonne et dûe forme). Au contraire, c’est un enfermement de plus…

- Le juge n’est pas psychiatre, il se garderait bien de remettre en question le jugement des médecins sur le fond. Par contre, on lui a expliqué que tout patient qui conteste le traitement est en « opposition », ce qui constitue déjà une preuve de « déni de maladie ».

- Les médecins y trouvent donc une voie bien pratique pour se décharger de leurs responsabilités, puisque « c’est le juge qui décide ». Et alors on voit défiler les patients dans le bureau du juge, accompagnés d’un soignant : « on vous amène Mme X »…

- On vous octroie un avocat commis d’office une semaine avant, mais qu’on ne peut pas contacter avant. Le jour de l’audience, c’est 15 minutes pour faire connaissance et se préparer, et ceci « dans les cases »…

- Ce qui est très alarmant, c’est qu’on ne trouve pas d’avocat en libéral, à part peut-être à Paris, et seulement pour un recours aux assises.

- Le juge prétexte qu’il ne peut lever le soin sous contrainte si c’est à la demande du directeur de l’établissement. Or, toutes les demandes de mise en soins sous contrainte passent par l’approbation du directeur. Tout le monde se donne bonne conscience, donc ;

- Une fois l’audience terminée (10 minutes), où l’on se voit déstabilisé, accusé et mis en doute, le juge « ordonne » le maintien en hospitalisation complète et de la mesure de contrainte, ce qui confère force de loi aux médecins (et donc une impunité totale) et SURTOUT donne encore plus de poids à la mesure.

- Inutile de préciser que si on était encore crédible avant, on ne l’est plus du tout et c’est définitif. Si on refuse de signer la feuille ou de comparaître, c’est pire, et on s’attire les foudres des médecins et du personnel soignant, qui vous mettent la pression, vous humilient et vous maltraitent. On ne peut pas non plus refuser que l’audience ait lieu.

- Le juge sait pertinemment qu’il s’agit d’une volonté potitique de faire taire les « récalcitrants » par voie chimique et coercitive. Il y adhère donc pleinement.

Pourquoi je suis contre les traitements forcés :

J’insiste sur le fait que les psychiatres hospitaliers ont les pleins pouvoirs sur le choix et le dosage des traitements, il ne s’agit JAMAIS d’un consentement éclairé. La « balance bénéfice-risque » est toujours de leur côté, même en cas de surdosage, même si la personne prend déjà 17 médicaments et pèse 200kg (ce qui est le cas d’une amie à qui on a donné Zyprexa ET Xeroquel suite à quoi elle a fait un accident vasculaire cérébral). Ils ne sont jamais responsables des effets secondaires non plus et vous orientent « gentiment » vers votre généraliste…

De plus, c’est toujours les médecins qui « décident » à votre place si vous allez bien ou non, et ce, même s’ils ne vous connaissent pas ou vous on vu seulement 5 minutes…

L’effet pervers de la chose, c’est que c’est tellement insupportable d’être enfermé et camisolé chimiquement qu’au bout d’un mois, on fait semblant d’aller mieux, on renie ses opinions et on arrête de se plaindre des effets secondaires pour pouvoir sortir, sous peine de se voir diagnostiquer en plus des « troubles du comportement » et un « déni de la maladie»…

J’AI ETE TORTUREE : au Zyprexa (surdosage), au Solian, au Tercian, au Risperdal (8 mg pour un poids de 50 kg), à l’Haldol (90 gouttes par jour) et « shootée » au Valium (40mg!)…

Le médecin et le personnel infirmier refusaient de prendre en compte : les troubles de l’élocution, tremblements, convulsions, dyskinésies, impatiences insupportables, angoisses mortelles, envie de mourir et tortures psychiques (« enfer » mental) qui ont apparu immédiatement et ont même empiré avec le temps. Je me suis battue en vain en plaidant que les neuroleptiques anesthésient la conscience, font perdre la mémoire, rendent docile et influençable, rendent dépressif et encore plus anxieux, affectent les capacités intellectuelles et détruisent l’âme.

J’ai également été mise plusieurs fois en isolement avec violences de la part du personnel ET des employés de la sécurité, alors que je n’ai JAMAIS été agressive. J’ai été mise sous contention, j’ai été déshabillée de force, j’ai été déshydratée, humiliée, bafouée, maltraitée…

Aujourd’hui, même si j’ai droit à un traitement moins inhumain, l’Abilify en injectable (après une 4ème tentative de suicide), je reste « accro » au Valium, traumatisée et toujours en alerte, dans l’angoisse de manquer à mes « obligations » ou de faire mauvaise impression, sans parler de l’absence totale de perspectives, de motivation et de joie dans ma vie, sans parler de ma vie affective qui est une misère (mort spirituelle, isolation, dépression, anxiété…).

Ma carrière artistique, qui avait débuté avec succès, a été définitivement brisée pendant mes meilleures années (la trentaine) et je suis aujourd’hui dans l’incapacité de créer alors qu’avant je foisonnais d’idées et me donnais les moyens pour les mettre en œuvre. Il est également trop tard et trop compliqué pour moi maintenant pour devenir mère.

Je vis dans la précarité à la charge de l’Etat.

Pourquoi j’ai toujours été opposée à leurs « diagnostics » pathologisants :

Je suis une personne ayant vécu les pires traumatismes dans la petite enfance (viols et abus, harcèlement), dont la plupart des souvenirs sont remontés plus de trente ans après, ce qui a grandement affecté mon équilibre psychique. J’ai malheureusement dû constater que, d’après les psychiatres (pour autant qu’ils m’aient crue…), il n’y aurait aucune relation de cause à effet entre ce que j’ai subi et mes troubles (!), ce qui est tellement énorme et risible qu’on aurait plutôt envie d’en pleurer…

J’ai pu constater, à l’instar de la Dre Muriel Salmona, seule psychiatre en France à ma connaissance qui aborde la souffrance psychique sous l’angle du trauma, qu’en France, aucune prise en charge spécifique n’est prévue ou proposée, et après 8 ans de psychiatrie, aucun médecin à ce jour ne m’a diagnostiqué un syndrôme de stress post-traumatique avec dissociation, ce qui pourtant devrait être le cas après des viols dans la grande majorité des cas selon la Dre muriel Salmona ( Association Mémoire Traumatique et Victimologie ). Je n’ai quasiment jamais pu faire de travail thérapeutique avec un psychiatre.

Quant à leur diagnostic de schizophrénie, il n’a jamais été étayé, expliqué ou argumenté, et mon dossier a été établi sur des « observations » des médecins et de simples « impressions » du personnel soignant… J’ai constaté également que parler de spiritualité conduisait immanquablement à un diagnostic de « délire mystique », donc, selon eux, de schizophrénie.

J’en conclus que l’enfermement et leurs mauvais soins n’ont fait qu’en rajouter à mes traumatismes, je ne crois pas un seul instant que leurs maladies imaginaires résultent d’un déséquilibre chimique dans mon cerveau ou d’une quelconque « maladie » biologique, je sais que les effets des neuroleptiques sont catastrophiques à long-terme et je suis totalement en accord avec de nombreux anti-psychiatres à l’international, dont le Dr. Peter Breggin, Joanna Moncrieff, David Healy, Robert Whitaker, Thomas Szazs, Peter Goetzsche et autres… (cf. le site madinamerica.com).

CONFORMEMENT À LA CONVENTION DES NATIONS UNIES SUR LES DROITS DES PERSONNES HANDICAPÉES, ARTICLES 12, 14 ET 15, TEL QU’INTERPRÉTÉ DANS L’OBSERVATION GÉNÉRALE NO. 1 ET LES LIGNES DIRECTRICES SUR L’ARTICLE 14, ET AUX PRINCIPES DE BASE ET LIGNES DIRECTRICES PUBLIEES PAR LE GROUPE DE TRAVAIL SUR LA DETENTION ARBITRAIRE DE L’ONU, PRINCIPE 20 ET LIGNE DIRECTRICE 20, JE PLAIDE POUR L’ABOLITION TOTALE DE LA PSYCHIATRIE COERCITIVE ET DES TRAITEMENTS FORCES.

JE REVENDIQUE TOUS MES DROITS A LA PERSONNE EN TANT QUE FEMME MAJEURE PROTEGEE, PERSONNE HANDICAPEE, EN PARTICULIER LE DROIT INALIENABLE DE DISPOSER PLEINEMENT DE MON CORPS ET DE MON ESPRIT SANS CHIMIE IATROGENE, DE MA LIBERTE INCONDITIONNELLE.

JE CONSIDERE LA PSYCHIATRIE INSTITUTIONNELLE ET SES PRATIQUES COERCITIVES COMME UN CRIME CONTRE L’HUMANITE, UNE ATTEINTE A LA DIGNITE ET A LA LIBERTE DE PENSEE

Pink Belette, Mars 2016

****

Psychiatry in France, NO-RIGHTS-ZONE (By Pink Belette)

A french patient under forced commitment makes her « audit assignment » as part of the campaign to support CRPD absolute prohibition of commitment and forced treatment

Why I am against commitment and forced treatment :

One could believe that, in the land of liberty, one is still entitled to his or her physical and moral integrity.

Experience proves it wrong. It is impossible for anyone to escape forced commitment (so-called « care on demand of a third party » or « imminent danger »).

It’s already a done deal if : one person asks for it (family, neighbour…), one is « not well », unsettled, agitated, « not stable », gets angry, is depressed, on the defensive, « in opposition », exuberant, emaciated, bulimic, shit smoker, drugged…

It is sufficient if one refuses hospitalization or a treatment for the doctors to relieve each other in order to enforce commitment. Once hospitalized, it is been made perfectly clear that one looses his or her personal rights, only argument is : « now we are responsible of you for EVERYTHING »… Thus, towards the « patient », nobody is responsible of anything…

Since the « Bachelot law » of July 5th 2011, particularly if one has something to object, be it diagnose or treatment, it is then after being out of hospital that one cannot get rid of commitment, which is most perverse : forced injections, mandatory appointments with an non-chosen clinical psychiatrist (or, best case, with a choice between two doctors).

And, worst of all : if one refuses to go to the assigned medical center of one’s district, the police comes to pick one up at home and rehospitalization is mandatory with an increased commitment that is even more coercive (« on demand of the State »), on a longer lapse of time and with no authorization to communicate with the outside (!) until they succeed to break one’s will and reduce one to nothingness… It so happens that people loose their home and « live » in psychiatry (sometimes for decades, see Dimitri Fargette’s case)…

I witness : in France, there is really matter to worry about…

- There is no alternative to institutional psychiatry (lobbying of psychiatrists AND pharmaceutical industry against other forms of therapies) ;

- No antipsychiatric litterature nor culture (no « survivors »…)

- The « College of Psychiatrists » who suspends : every psychiatrist « not aligned » with this consensual system (according to Dr. O.G, liberal psychiatrist and former head of clinic);

- The « College of psychiatrists » suspending : a psychiatrist responsible for the death of a patient… only for two weeks (see the case of young patient Florence Edaine)

- The « Guardianship mafia » : every patient who is repeatedly hospitalized is automatically placed under guardianship under a certain degree (without consent, it is being reinforced…)

- Single mothers get their children robbed and placed immediately after a diagnosis of mental illness is established, never one scandal about this…

- Women in age to bear a child are being strongly recommended a contraception, with a wink that their child would be taken away from them anyway. What they are not being told is that all neuroleptics pass the placenta barrier, that’s why i have heard of so many miscarriages from women under treatment. A quote from a nurse : « pregnant women are given Haldol, which proves it’s little nocivity » (!). Never one study about that nor mediatic scandal.

- Closed wards full of depressive people who are not in « immediate danger » and are feeling bad mainly because they are being given for example 4 (!) antidepressants at a time…

- An always occupied isolation chamber (so-called « intensive care chamber »!), which participates to the « folklore »…

- « Once subscriber, always subscriber » : treatments one can NEVER withdraw from ;

- No long-term study on psychotropic medication… (All so-called studies are biased)

- No recourse in case of even flagrant psychiatric abuse (internal system of « mediation » obsolete : it’s a very bad idea to write a letter to the director of the institution…)

Why I am against this new system of « Judge of Liberties and Detentions » (related to the law of september 27th 2013) :

They are making believe it is a recourse. I was proved wrong, except for instance on a technicality (which almost never happens, because it’s in the psychiatrists’ interest that the procedure goes well and in due form). On the contrary, it’s in the sense of more legal coercion…

- The judge is no psychiatrist, he would never ever put into question the judgment of the physicians concerning the core. Thus, he has been briefed about the « fact » that any patient who opposes treatment is « in opposition », which establishes already a proof of « illness denial » (and as a proof of illness itself).

- Therein it has been found a very practical way for doctors to be discharged of their responsibilities, as « it’s the judge who decides ». And now, bunches of patients are being spotted filing up before the judges’ office, escorted by a nurse : « we bring you Ms. X »…

- Patients get a mandated advocate one week before the audience, but who cannot be contacted in advance. At audience day, it’s 15 minutes to meet and prepare, and, of course, in a « formated » way.

- Very alarming is the fact that no liberal advocate is to be found for psychiatric abuse pleas, except maybe in Paris, and mostly for a recourse before the Court of Assize.

- The judge pretends he cannot lift the forced commitment because it’s asked for by the hospital director. Yet, all demands for forced commitment have to be validated by the director. Hence everyone gives him- or herself a good conscience there ;

- Once the audience done (10 minutes), where one gets destabilized, accused and doubted of, the judge « orders » the maintaining of the person in complete hospitalization and of the measure, which confers force of law on the doctors (hence, total impunity).

- Not to mention the fact that if one still had credibility before, it’s no longer the case and irreversible. If one refuses to sign the convocation or to attend the audience, it’s worse, and one is being bullied by staff members and doctors alike, who put one under pressure, humiliates one… One also cannot refuse the audience being held despite of one’s absence.

- The judge knows pretty well that it’s a political will to make silent the « opponents » of the system, chemically and coercively. He therefore fully concurs with it.

Why I am against forced treatment :

I insist on the fact that hospital psychiatrists are almighty regarding the choice and dosage of treatments, it’s never about an « informed consent ». The « benefit- risk balance » is always on their side, even in case of overdosage, even if the person already takes 17 meds and weighs 400 pounds (which is the case of a friend to whom was administered Zyprexa AND Seroquel after which she had a cerebral attack with impairment). They are also never responsible for side effects and, in case of complaint, derefer to one’s generalist physician…

Thus, it is always them who « decide » on one’s behalf if one is well or not and this, even if they don’t know the person or have seen him or her only five minutes…

Perverse effect of the thing : it’s so unbearable being locked up and silenced chemically, that, after a month, one pretends to feel better, disavow his or her opinions and stops complaining about side effects in order to get out, knowing that otherwise one will be diagnosed behavioural troubles and « illness deny »…

I WAS TORTURED : with Zyprexa (overdosis), Amisulpride, Cyamemazine, Risperdal (8 mg for a weight of 100 pounds), Haldol (90 drops a day) and « shooted » with Valium (40mg!)…

The doctors and staff refused to take into account : speaking troubles, heavy trembling, convulsions, dyskinesia, unbearable akathisia, heavy existential fear, wish to be dead and psychical tortures (mental « hell ») which appeared immediately and even worsened as time went by. I fought in vain, pleading that neuroleptics anesthetize consciousness, occasion memory loss, make one docile and influentiable, make depressive and even more anxious, impair one cognitively and destroy the soul.

I was also put into solitary confinement several times with violences from the staff AND security agents, despite the fact I have NEVER been even agressive. I was put under contention, was violently undressed, dehydrated, humiliated, spoliated, mistreated…

Today, even if I get a « less inhumane » treatment – Abilify retard injection – (after a 4th suicide attempt), I remain addicted to Valium, traumatized and always on alert, fearing to miss my « obligations » or to make bad impression, without mentioning total absence of perspectives, motivation or joy in life, without mentioning my affective life that is a misery (spiritual death, isolation, depression, anxiety…).

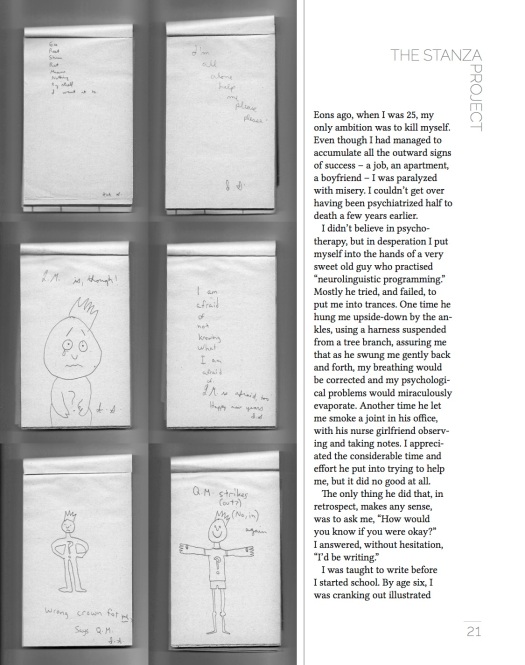

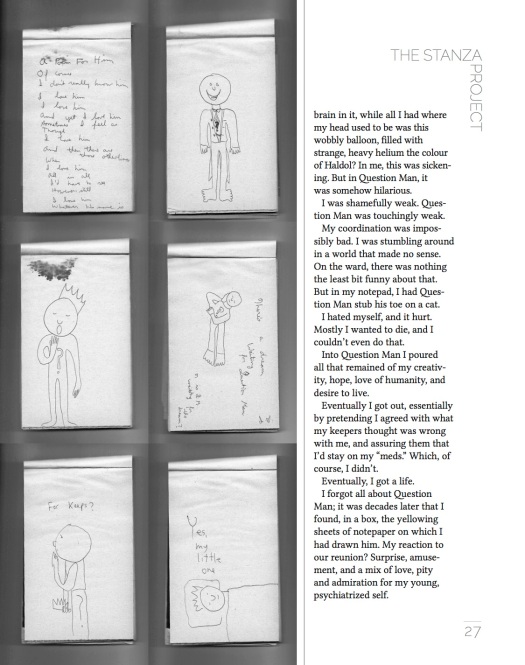

My artistic career, which finally started with success has been definitively broken during my best years (in my 30′) and today I am totally unable to create despite the fact that before, I had thousands of ideas and was giving a great deal to put them into meaningful use. It is also too late and too complicated for me now to become a mother.

I live in precarity at the charge of the State.

Why I was always opposed to their pathologizing « diagnoses » :

I’m a person who endured the worst traumas in early childhood (rape and abuse, mobbing…), while most memories came up again more than 30 years afterwards, which greatly affected my emotional balance. I had unfortunately to experience that, according to psychiatrists (if they even believed me), there would be no cause-to-effect relationship between what I had to bear and my troubles (!), which I find so enormous and stupid that one would rather cry…

I had to notice, alike Dr. Muriel Salmona – only psychiatrist in France knowingly approaching psychical suffering under the perspective of trauma – that in France, no specific caretaking is being proposed nor planned, and after 8 years of psychiatry, not one physician has diagnosed me a post-traumatic stress disorder with dissociation which, according to Dr. Muriel Salmona (« Association Mémoire Traumatique et Victimologie ») is the case after rape and abuse.

I could almost never do a therapeutic work with a psychiatrist.

Regarding their diagnosis of schizophrenia, it has never been illustrated, explained or argumented, and my medical records have been established on mere « observations » from the doctors and sheer « impressions » from the staff…

I also came to the conclusion that to actually speak about spirituality would eventually always end in them diagnosing a « mystical delirium » and, as such, schizophrenia.

My conclusion is that their imprisoning and bad treatments have done none but to aggravate my traumas and personal issues, I don’t believe a second that their imaginary « diseases » result in a chemical imbalance in my brain or an unknown « biological » illness, I know that neuroleptics and affiliated meds are catastrophic in the long-term (causing brain damage) and I totally agree with numerous anti-psychiatrists internationally, such as the Drs. Peter Breggin, Joanna Moncrieff, David Healy, Robert Whitaker, Thomas Szazs, Peter Goetzsche and others… (see on madinamerica.com).

IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES, ARTICLES 12, 14 AND 15, AS INTERPRETED IN GENERAL COMMENT NO. 1 AND THE GUIDELINES ON ARTICLE 14, AND WITH THE BASIC PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES OF THE UN WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION PUBLISHED IN 2015, PRINCIPLE 20 AND GUIDELINE 20, I SPEAK IN FAVOUR OF ABSOLUTE PROHIBITION OF COERCIVE PSYCHIATRY AND FORCED TREATMENT.

I RECLAIM ALL MY RIGHTS TO PERSONHOOD AS A DISABLED ADULT WOMAN UNDER PROTECTION, IN PARTICULAR THE INALIENABLE RIGHT TO DISPOSE ENTIRELY OF MY BODY, MIND AND SOUL WITHOUT IATROGENIC CHEMICALS AND MY UNCONDITIONAL LIBERTY.

I CONSIDER INSTITUTIONAL PSYCHIATRY AND ITS COERCIVE PRACTICES A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, A SEVERE HARM TO DIGNITY AND TO FREEDOM OF THINKING.

Pink Belette, March 2016