CAMPAÑA DE APOYO A LA CDPD COMPROMISO CON LA PROHIBICIÓN ABSOLUTA DE LA PRIVACIÓN DE LA LIBERTAD Y EL TRATAMIENTO FORZADO DE LAS PERSONAS CON DISCAPACIDAD PSICOSOCIAL

Señores del Comité sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad:

Solicito tengan a bien dar la merecida atención a todas las voces que elevamos los actores socio-políticos que pedimos la prohibición absoluta de la privación de la libertad por motivos de discapacidad psicosocial.

Lucila López

Usuaria y sobreviviente de la psiquiatría en Argentina.

(también se puede leer en https://sodisperu.org/2016/03/22/aporte-a-la-campana-prohibicionabsoluta-por-lucila-lopez-usuaria-y-sobreviviente-de-la-psiquiatria-en-argentina/)

CAMPAÑA DE APOYO A LA CDPD ART. 14 LL-MARZO14 2016 (doc)

Intentaré exponer los motivos sobre la importancia de obtener el apoyo necesario para que la Campaign to Support CRPD Absolute Prohibition of Commitment and Forced Treatment – Campaña de apoyo CDPD COMPROMISO CON LA ABSOLUTA PROHIBICIÓN DE LA INTERNACIÓN Y EL TRATAMIENTO FORZADO iniciada por la Dra. Tina Mikowitz resulte como positivo fortalecimiento al momento de las Observaciones Generales a favor del irrestricto cumplimiento del artículo 14 inc. y todos los artículos vinculantes.

Artículo 14

Libertad y seguridad de la persona

- Los Estados Partes asegurarán que las personas con discapacidad, en igualdad de condiciones con las demás:

a) Disfruten del derecho a la libertad y seguridad de la persona;

b) No se vean privadas de su libertad ilegal o arbitrariamente y que cualquier privación de libertad sea de conformidad con la ley, y que la existencia de una discapacidad no justifique en ningún caso una privación de la libertad.

2. Los Estados Partes asegurarán que las personas con discapacidad que se vean privadas de su libertad en razón de un proceso tengan, en igualdad de condiciones con las demás, derecho a garantías de conformidad con el derecho internacional de los derechos humanos y a ser tratadas de conformidad con los objetivos y principios de la presente Convención, incluida la realización de ajustes razonables.

“El Comité sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad reafirma que la libertad y la seguridad de la persona es uno de los derechos más preciosos a que tiene derecho. En particular, para las personas con discapacidad, y en especial las personas con discapacidad intelectual y discapacidad psicosocial tienen derecho a la libertad en conformidad con el artículo 14 de la Convención. En él se especifica el alcance del derecho a la libertad y a la seguridad de la persona en relación con las personas con discapacidad, prohíbe toda discriminación basada en la discapacidad. De este modo, el artículo 14 se relaciona directamente con el propósito de la Convención, que es garantizar el disfrute pleno e igual de todos los derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales a todas las personas con discapacidad y promover el respeto de su dignidad inherente.”[i]

__________________

Nada se puede pensar por fuera de un contexto. El tema propuesto es un tema ineludible en términos de un pensamiento con eje en los Derechos Humanos.

Escribir en Argentina sobre la necesidad de garantizar la prohibición absoluta de privar de la libertad a las personas con discapacidad en nombre de tratamientos impuestos, forzados, en contra de la propia voluntad, es escribir en un contexto en el que el respeto a los DD.HH. es ostensiblemente violado provocando actualmente una seria preocupación para el CIDH, específicamente por una presa política. En relación al tema, es significativo que Estela de Carlotto[ii] haya preguntado -¿Cómo se puede decir que está muy bien una mujer presa? Y calificó esa afirmación de la más alta autoridad del país como “una barrabasada”. El texto completo es el siguiente:

“La barrabasada[iii]que dijeron es que la habían visitado en la cárcel y que estaba muy bien. Fue violento. ¿Cómo se puede decir que está muy bien una mujer presa?

Me permito hacer un parangón y preguntar: ¿Cómo se puede decir que está bien una persona privada de la libertad (presa) por su discapacidad?

Estoy a favor de la prohibición absoluta de la privación de la libertad involuntaria y tratamientos forzados de las personas con discapacidad psicosocial y el compromiso para con todos comienza en el ejercicio para mi propia vida de ese derecho y el Art. 14 de la CDPD me autoriza a exigir el cumplimiento de la norma jurídica.

Mis argumentos son en nombre propio a partir de mis experiencias y la observación de la experiencia de otros, articulando mi condición de usuaria y sobreviviente de la psiquiatría, mi visión como profesional dedicada a la prevención en Salud Mental y Derechos Humanos y como familiar, en tanto soy madre de un hombre que siendo niño y hasta entrada su adultez, necesitó de la protección de sus derechos incluido el derecho a la salud y el derecho a la salud mental.

Estuve privada de la libertad y en contra de mi voluntad por última vez entre el 5 de julio de 2014 y el 12 de enero de 2015. La cuarta vez en mi vida y la más extensa en tiempo.

Esa misma barrabasada “que me encontraban muy bien” la escuché de familiares y amigo/as y me mantuve en un total mutismo.

Desde el año 2011, la crisis anterior con internación contraria a mi voluntad, comencé a guardar mutismo absoluto delante de los que apoyaron esa medida y están dispuestos a apoyarla de nuevo.

¿Por qué guardar mutismo?

Por lo intolerable que resulta la alianza entre los profesionales de la salud mental y familiares y/o amigos:

- Ignoran la CDPD.

- No tienen en cuenta el respeto a la persona como un igual.

- Prevalezcan sobre mi cuerpo y sobre mi psiquismo[iv] decisiones ajenas violatorias de todos

- Los siguientes derechos enumerados en la CDPD (Ley 26.378) que es parte del cuerpo jurídico de la Constitución Nacional de Argentina.

Artículo 5º

Igualdad y no discriminación

Artículo 12

Igual reconocimiento como persona ante la ley[v]

Artículo 14

Libertad y seguridad de la persona

Artículo 15

Protección contra la tortura y otros tratos o penas crueles, inhumanos o degradantes

Artículo 17

Protección de la integridad personal

Artículo 18

Libertad de desplazamiento y nacionalidad

Artículo 19

Derecho a vivir de forma independiente y a ser incluido en la comunidad

Artículo 22

Respeto de la privacidad

Artículo 23

Respeto del hogar y de la familia

1.C) Las personas con discapacidad, incluidos los niños y las niñas, mantengan su fertilidad, en igualdad de condiciones con las demás.

Artículo 24

Educación

Artículo 25

Salud

Artículo 27

Trabajo y empleo

Artículo 28

Nivel de vida adecuado y protección social

Enumerados todos los derechos vinculantes que se violan a partir de la falta de respeto al art. 14, argumentaré los motivos por los que pido la PROHIBICIÓN ABSOLUTA DE LA PRIVACIÓN DE LA LIBERTAD INVOLUNTARIA.

En Argentina, exigir la prohibición absoluta de la libertad involuntaria por motivos de discapacidad psicosocial encuentra un horizonte de futuro posible con la prohibición establecida por la LNSM –Ley 26.657 – de la creación de nuevos manicomios públicos y privados en todo el territorio de la Nación y el cierre definitivo de todos para el año 2020.

La privación forzada de la libertad, -o internación involuntaria- o no por motivos de discapacidad psicosocial es claramente una acción discriminatoria, de acuerdo a la legislación argentina y el marco jurídico internacional:

“La discriminación es el acto de agrupar a los seres humanos según algún criterio que lleva a una forma de relacionarse socialmente. Concretamente, suele ser usado para hacer diferenciaciones que atentan contra la igualdad, ya que implica un posicionamiento jerarquizado entre grupos sociales 1, es decir, cuando se erige un grupo con más legitimidad o poder que el resto.

En el año 1988, se sancionó la Ley Nº 23.592 sobre Actos Discriminatorios que en su Artículo 1º reconoce como discriminación cualquier impedimento o restricción del pleno ejercicio “sobre bases igualitarias de los derechos y garantías fundamentales reconocidos en la Constitución Nacional […] por motivos tales como raza, religión, nacionalidad, ideología, opinión política o gremial, sexo, posición económica, condición social o caracteres físicos”. Asimismo, el documento titulado “Hacia un Plan Nacional contra la Discriminación”, aprobado por Decreto Nº 1086/2005.Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo. (INADI ¿Qué es la discriminación?).-

La privación de la libertad involuntaria a partir de la CDPD se constituye en un acto de violación de DD.HH.y el Estado se debe responsabilizar de ello[vi] pues aún cuando en Argentina ha ratificado la CDPD y le ha dado status constitucional:

La Ley Nacional de Salud Mental Ley 26.657- que es considerada una Ley de Salud Mental modelo por todos los avances dirigidos hacia el nuevo paradigma social y del respeto de los DD.HH. de las personas con discapacidad, incurre en la violación del artículo 14 considerando que:

La LNSM En el Capítulo VII, Art. 20) contempla de la internación involuntaria: “Ley 26.657 ARTICULO 20. — La internación involuntaria de una persona debe concebirse como recurso terapéutico excepcional en caso de que no sean posibles los abordajes ambulatorios, y sólo podrá realizarse cuando a criterio del equipo de salud mediare situación de riesgo cierto e inminente para sí o para terceros. Para que proceda la internación involuntaria, además de los requisitos comunes a toda internación, debe hacerse constar… “

Acá encontramos un argumento a favor de la internación involuntaria contraria a la letra de la CDPD y su art. 14.-

La idea que prevalece en este artículo de la LNSM es la del paradigma del MMH., encuentra gran receptividad tanto en los profesionales de la salud como así también de familiares. Desde la implementación de la LNSM no se cumple con el art. 14 de la CDPD pero tampoco se cumple con lo que estipula la LNSM en el Art. 20, pues la concepción de recurso terapéutico excepcional se convierte en letra muerta de la ley y es una mera formulación administrativa o de buenas intenciones si se pueden llamar así a los argumentos esgrimidos para privar de la libertad en forma involuntaria.

Este acto discriminatorio y violatorio de DD.HH. goza de un consenso intelectual que supone el encierro de las PcD como “un corte, una instancia de reordenamiento subjetivo”.

El “corte subjetivo” se produce en la PcD en el momento que se denomina crisis y no necesita de ser privada de la libertad. Se puede “volver a la vida plena” en la vida plena de poder padecer un “corte” de “conexión con la realidad” si se brindan todos los apoyos y ajustes necesarios para tornar viable la vida en la comunidad.

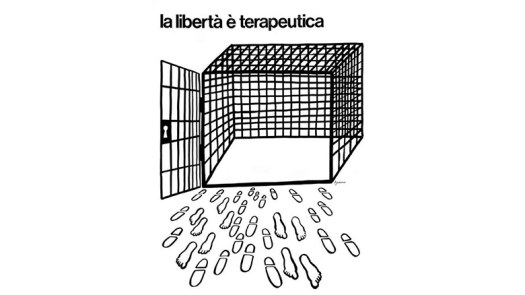

No podemos ser discriminados por ser personas con discapacidad psicosocial y considerar terapéutico el encierro y el aislamiento que es una práctica iatrogénica al igual que la medicación forzada.

Vuelvo sobre la necesidad de contextuar el texto.

En Argentina hay una gran resistencia de parte de los profesionales de la salud mental a mencionar el tema discapacidad ligado al tema de las problemáticas de la salud mental.

En este presente inmediato, hablar de Derechos Humanos en Argentina articulados con la Salud Mental o con cualquier otro aspecto de la vida de las personas en general es un tema que pone en cierto peligro a quien se anima a denunciar.

Mi opinión al respecto después de muchos años de indagar el tema es que los profesionales de la salud mental junto a una gran parte de la población no aceptan que las PcD psicosocial somos personas con el reconocimiento de la dignidad y el valor inherentes y de los derechos iguales e inalienables de todos los miembros de la familia humana.

No aceptan la condición de sujeto de derecho en igualdad de condiciones que invoca la CDPD y esto es especialmente notorio al observar que en Argentina, la LNSM Nro. 26.657, es despreciada e incumplida por la corporación médico-psiquiátrica quienes consideran que debe ser derogada porque entre algunos de sus acertados artículos se promueve la interdisciplinariedad, el cierre de la totalidad de los manicomios públicos y privados en todo el territorio nacional y también promueve las internaciones en hospitales generales (considerando el respeto a quien desee ser internado de forma voluntaria).-

El primer obstáculo para hacer notar que el art. 20 de la LNSM 26.657 viola el Art. 14 de la CDPD es que los profesionales de la salud y de la salud mental, los trabajadores sociales y un amplio espectro de la justicia y una enorme masa de la población en general no están dispuestos a respetar los DD.HH. de las PcD psicosocial y que las lógicas manicomiales prevalecen en el imaginario social sobre los avances y cambios que en la materia se vienen discutiendo a nivel mundial.

La mayoría de las internaciones que se realizan son involuntarias y en general no se cumplen los pasos que la LNSM dispone para estos casos. Una ingeniería perversa de mecanismos burocráticos actúa evitando que la información llegue a la justicia en tiempo y forma, haciendo permanecer a una persona hasta por cuatro meses internada sin haber ejercido ni el consentimiento informando sobre el tratamiento que le administran arbitrariamente ni tuvo acceso a un abogado defensor como lo estipula la LNSM.

Es de mi particular interés las internaciones involuntarias de niños/as-adolescentes y jóvenes por motivos vinculados al consumo problemático de sustancias psicotrópicas en instituciones aberrantes con la anuencia de sus familias y también, en el otro extremo del arco, a las personas mayores y la naturalización de su institucionalización en lugares llamados geriátricos, residencias u hogares que también, con un proceder perverso, ocultan las problemáticas de discapacidad mental más propias de la ancianidad, del deterioro cognitivo que puede aparecer con el avance de la edad y otras formas de discapacidad mental que no son atendidas en su particular singularidad y sí son privadas de la libertad casi siempre sin su propio consentimiento.

Entonces sufren internaciones involuntarias y así se violan los DD.HH. de:

Niñas, niños, adolescentes mujeres y hombres, jóvenes, adulta/os y ancianas/os declarados o no personas con discapacidad mental por razones vinculadas a problemáticas de la salud mental.

En todos estos casos prevalece el concepto discriminatorio que no tenemos igual reconocimiento como persona ante la ley.

Partiendo de esta premisa comenzaré a exponer de qué manera la internación, la privación de la libertad involuntaria es una verdadera violación de DD.HH. que comete el Estado atropellando derechos y aumentando la discapacidad y propiciando el empobrecimiento de las personas afectadas en sus intereses económicos, sociales y culturales.

La internación involuntaria es iatrogénica:

- en lugar de un resultado positivo para la salud, la privación de la libertad junto a tratamientos con drogas psiquiátricas forzados generan enfermedades, atenta contra la salud psíquica y física de la persona y la despoja del ejercicio de un sinfín de derechos aún cuando no se haya restringido su capacidad jurídica y esto también en internaciones –involuntarias o no- a corto plazo.

La realidad de una gran mayoría es que su capacidad jurídica está restringida.

En Argentina actualmente hay más de 20.000 personas privadas de la libertad en manicomios públicos y privados, según datos poco fidedignos, en su mayoría hombres entre 20 y 40 años que en su mayoría llevan un promedio de 15 a 20 años de privación de la libertad. De esa mayoría un número elevado entró en el circuito de las internaciones por consumo problemático de sustancias psicotrópicas siendo el alcohol la que encabeza el listado de ellas, que no es una droga ilegal.

Es muy llamativo que los datos oficiales oculten las cifras que puedan informar la cantidad de niñas y mujeres privadas de la libertad de manera involuntaria que hay en el país y me animo a decir que debe ser significativamente superior a la cantidad de hombres privados de la libertad.

En todos o en casi todos esos casos, ya sea en el ámbito público como en el privado la violación al art. 14 de la CDPD conlleva la violación de todos los otros artículos de la CDPD enumerados anteriormente.

La libertad y la seguridad de la persona son avasalladas y entonces su integridad en el más amplio concepto de la palabra también.

Hay una gran parte de la población privada de la libertad por motivos de discapacidad psicosocial que desconocen su verdadera identidad. Están desprovistas de documentos de identidad. No tienen contacto con familiares desde hace años y han sido separados de su comunidad.

Muchos, con estudios iniciados, han perdido el derecho a continuarlos, otros directamente no acceden porque comienzan el derrotero de las internaciones psiquiátricas durante la infancia. Conocí en el manicomio a un hombre mayor de cincuenta años que estaba internado desde los cinco años, desde su primera infancia… y allí murió.

Las instituciones psiquiátricas tienden a incurrir en una doble violación al Derecho a la Salud, en tanto:

- La privación de la libertad involuntaria o no, es iatrogénica.

- La PcD psicosocial internada en instituciones psiquiátricas suele carecer de verdadera atención médica en otros aspectos que su salud requiera: la aparición de síntomas de un quebrantamiento de la salud física suele ser ignorado, “interpretado” como síntoma o manipulación de la PcD desde el discurso médico-psiquiátrico y también, se le niega el acceso a profesionales de otras especialidades. Ejemplo: la asistencia de un otorrinolaringólogo… “porque es incómodo el traslado a un servicio especializado” y la persona debe aceptar y tolerar no ser atendida. Esta triste realidad trae aparejado resultados muy graves: muertes por enfermedades tratables tanto en la población femenina como en la masculina. También se les niega el acceso a los tratamientos indicados por médicos especialistas en el caso que tengan acceso a una consulta.

Todo esto está reñido con el principio básico del ser en igualdad de condiciones.

La vida privada de la libertad “no es vida”.

La privación de la libertad acompañada por el tratamiento forzada con drogas psiquiátricas provoca una especie de muerte psíquica.

Los acontecimientos de la vida cotidiana bajo los efectos de la medicación psiquiátrica –forzada o no, dentro y fuera de la internación- se perciben como si se mirara a través de un vidrio esmerilado, la voz de los otros llega a uno con un efecto retardado, y nuestros pensamientos también resultan lentos bajo los efectos de las drogas psiquiátricas. El contacto con el otro, con el afuera, está “mediado” por una cortina invisible que ralentiza los movimientos por el cuerpo rigidizado y los sentidos aletargados.

Así, el otro, cualquiera que sea, nos percibe “raros” “distintos” y los médicos aseveran que es el “devenir propio de la enfermedad diagnosticada” negando de cuajo que ese estado es el efecto de la privación de la libertad y del tratamiento químico forzado.

Con la privación de la libertad involuntaria, suele aparecer un estado de apatía profundo, un gran desinterés por todo… en mi experiencia esta apatía y el desinterés –incluso de hablar y permanecer en un mutismo absoluto- lo produce la imposibilidad de comprender que para el círculo de personas de mi afecto, esa situación fuera considerada buena, que dijeran que me “encontraban mejor”… si realmente esa es la mirada que tienen mis afectos cercanos, sean familiares o amigos, debo decir que no tienen registro alguno de las vivencias ciertas de humillación y maltrato que se viven en una internación.

Hay personas que estando internadas involuntariamente, hacen abandono de su aspecto físico y de su higiene. También eso es leído como un aspecto de “su enfermedad”… no se lee como un efecto iatrogénico de la privación de la libertad.

Los cambios a los que el cuerpo se ve sometido, desde el notorio aumento de peso con la pérdida de las formas propias del cuerpo y además, la falta de agilidad que provoca la medicación que rigidiza los músculos y el estado de “desconexión” que las mismas producen – y se aumenta notablemente con la privación de la libertad-, son otros aspectos que la persona padece, que pueden resultar motivo de vergüenza o mayor disminución de la estima.

La persona privada de la libertad, en un manicomio, tiene que poder evaluar estrategias de supervivencia y muchas veces, las elecciones son “el mal menor” y no lo que corresponde ni es justo ni a lo que se tiene derecho aún cuando se sea plenamente consciente de que se tiene derecho.

Cabe aclarar que una gran mayoría de la población internada desconoce todos sus derechos y además, cree que no los tiene. En las PcD psicosocial institucionalizadas durante muchos años en forma permanente o intermitente, se notan conductas propias de las personas sometidas a gran sometimiento y la faceta que muestran con claridad es la idea de “no tener derechos”

Así es muy poco probable que ellos luchen por una forma de vida independiente, el derecho a ser incluid en la comunidad en igualdad de condiciones porque se perciben así mismos como “personas enfermas”

Es común escuchar a adolescentes afectados a tratamientos -involuntarios o no- por consumo excesivo de drogas psicotrópicas, y en especial alcohol, decir “no tengo derecho a nada porque he consumido drogas” y ese discurso es avalado por los responsables de su rehabilitación y tratamiento y en cierta medida y en muchas oportunidades también ese concepto es sostenido por familiares, se suma a esto que los profesionales de la salud mental encuentran dificultades para aceptar que los problemas derivados del consumo excesivo de drogas legales o ilegales es un tema que debe ser abordado dentro del ámbito de la salud… y son enviados a lugares de encierro con un régimen propio y diría “sin ley” donde prevalece la ley del más fuerte que suele ser en general “un adicto recuperado” que impone tratos degradantes.

Así, son salvajemente humillados y denigrados, abusados sexualmente y de otras formas niñas/niños y adolescentes sometidos a trabajo solamente comparables a la tortura y la esclavitud en el marco de internaciones forzadas o no.

En relación a esta problemática de la salud mental el entramado es de una gran complejidad y la violación de DD.HH. es indescriptible.

Nadie que está privado de la libertad tiene la posibilidad de decidir un lugar de residencia por fuera del manicomio que le ha tocado en desgracia y en virtud de su status social o el de su familia…

La mayor cantidad de personas privadas de la libertad de modo involuntario lo son por problemas sociales y al mismo tiempo:

La mayor parte de las problemáticas llamadas “enfermedades mentales” provienen de problemas sociales no atendidos debidamente por el Estado y afectan de manera altamente significativa a la población de menos recursos.

Poblaciones importantes en las que, de generación en generación, han transcurrido sus vidas en situaciones de extrema pobreza sin conocimiento de los Derechos Humanos que los asisten si tienen la desgracia de “caer en el manicomio, no tienen salida”. Se patologiza la pobreza!!! Hay un perverso discurso que “dice que la persona no ha sido capaz de tener ingresos adecuados para su sustento y/o el de su familia y garantizar vivienda, educación y salud”.

Esa supuesta enfermedad de una persona: ¿cómo se llama cuándo el sistema de salud mental con la privación de la libertad –involuntaria o no- des-ancla a la persona de su vida, de sus bienes, de sus ingresos económicos, de su universidad o de su escuela de estudios primarios y así, la deja en un vacío de derechos y sobre eso la re-diagnostica?

No hay mayor factor discapacitante que la pobreza, el hambre, la falta de techo y de educación. Y eso puede ser un punto de partida o de llegada para una persona con discapacidad social.

También muchas personas que caen abruptamente en la pobreza como consecuencia de las crisis económicas que se conocen como “respuestas al humor de los mercados”, es decir: las crisis económicas resultado de propuestas políticas neoliberales y del salvaje capitalismo, arrojan a la “locura” y al intento de suicidio –cuando no a la muerte misma- a muchas personas que mantuvieron durante gran parte de su vida un status de vida acorde a los derechos propios de una persona trabajadora con derecho al trabajo, la salud y la vivienda como derechos básicos inalienables y esas personas, recalan en los manicomios con un diagnóstico de enfermos psiquiátricos pero en sus Historias Clínicas no constan las condiciones de existencia al momento de la internación ni sus antecedentes culturales, laborales, familiares y sociales, ni nada, absolutamente nada de su vida antes de haber sido calificado como enfermo/a psiquiátrico/a.

Con horror observo que la familia reproduce el sistema de pensamiento manicomial.

La misma familia termina violando el derecho al hogar y la familia.

Poco a poco se aleja hasta dejar en el abandono a la persona.

Se la priva de la familia, de los hijos y de los nietos.

La familia se aleja porque es estigmatizada y además no recibe psico-educación alguna para albergar al familiar que sufre y contribuir a su inserción en la comunidad. Todo lo contrario, siempre se acentúa el hecho que la persona está enferma, que su enfermedad es incurable y que con el tiempo estará cada vez peor.

Eso es verdad cuando a una persona la privan de la libertad, en forma involuntaria o no, porque todo lo que le va pasando no es consecuencia de su padecimiento espiritual, emocional o psíquico… es consecuencia del asilamiento tras los muros agudizado por la “droga- dependencia- inducida” y por la soledad impuesta, que llega a sus grados de tortura más elevado en las celdas de aislamiento o con la sujeción mecánica en los casos que la persona presente algún tipo de excitación motriz que bien pudo ser ocasionada por un ”medicamento” o por falta de una caricia… por un miedo extremo o por una profunda angustia que nadie parece dispuesto a aliviar con un acompañar en un cuerpo a cuerpo hasta que el terror disminuya.

¿Dónde están escritas las bases del encierro involuntario como forma de cura?

En la decisión de privar de la libertad a una persona con discapacidad psicosocial de manera forzada hay un pensamiento, hay una lógica “a priori” que dispone que esa persona “no tiene cura en su enfermedad” y es una persona gravosa para la comunidad a la que se atribuyen todo tipos de males para sí mismo y o para terceros y que merecen la condena del encierro. Esto subyace en el pensamiento de quienes ejercen autoridad sobre la PcD psicosocial y le restringen la vida y la sumen en una vida en su mínima expresión, carente de sueños y anhelos, de amor y de libertad.

En Argentina los manicomios en su mayoría cuentan con “dispositivos de inserción laboral” a los cuales las personas privadas de la libertad son “invitados” a participar. Esa invitación y la aceptación o no, lleva a aumentar la cantidad de etiquetas que una persona puede ir sumando en el encierro de acuerdo a lo que se llama la falta o no de “adherencia al tratamiento”. Si la persona acepta trabajar en un emprendimiento de inserción laboral intra-hospitalario, recibirá un peculio[vii]… una míseros centavos por su trabajo y si no acepta, se le calificará como a una persona “institucionalizada que no tiene voluntad ni interés en el trabajo” y con pocas posibilidades de su inserción en la comunidad.

Las personas que estando internadas nos preocupamos por nuestra situación laboral somos desmotivadas y se nos promueve un pensamiento basado en la imposibilidad de continuar con tareas “normales” y el “beneficio” de acceder a “pensiones por discapacidad”.

Sostener delante de un psiquiatra la firme decisión de continuar trabajando en el mercado de trabajo como un ciudadano más, es descalificado en sus palabras, se es tratado como una persona que niega su “incapacidad” y lo usual es que el médico psiquiatra desconozca absolutamente todo lo referido a esa persona: sus estudios, su historia laboral y su estándar de vida si se trata de un manicomio púbico y en uno privado, si la persona en situación de encierro tiene un estar en el mundo alivianado de preocupaciones económicas porque posee dinero suficiente… no es menos descalificado… solo que esa persona puede llegar a tener más posibilidades de una vida autónoma si es que los familiares no lo inhabilitan restringiendo su capacidad jurídica para hacer ellos, usufructo de los bienes económicos de la persona con discapacidad.

Ninguna persona que tenga como único sustento en Argentina una pensión por discapacidad puede acceder a una canasta básica de alimentos, ni a la vivienda ni a la salud, no puede tener una vida independiente y autónoma ni puede vivir con libertad en la comunidad porque sus ingresos económicos, que son considerados “un beneficio” social, no le permiten tener ninguna autonomía económica.

No existe un nivel de vida adecuado ni protección social verdadera.

Vuelvo sobre el rechazo en Argentina de parte de los profesionales de la salud por la noción de discapacidad de la “persona con padecimiento mental” en cualquiera de sus manifestaciones.

La discapacidad es una concepción que pone en cuestión a la tan preciada, tanto como despreciada “enfermedad mental” corriendo el eje de la enfermedad individual al eje de las barreras sociales que obstaculizan la libertad individual, lo que se da en llamar el cambio de paradigma.

Los aún hoy promotores de las lógicas manicomiales encuentran en la concepción de la discapacidad una herramienta que otorga derecho a quienes ellos le quieren negar -ya no los derechos- si no la vida misma condenándoles al encierro y al estado de ser muertos vivientes, verdaderos zombis que deambulan entre los muros sin más pregunta que si la inmunda comida llegó a la mesa o no… si alguien se acordó de su existencia y llegó de visita o no…

A las mujeres privadas de la libertad se les puede llegar a producir la esterilidad quirúrgica…de modo involuntario… como se las puede prostituir… o abusar sexualmente de ellas y provocarle embarazos no deseados y hasta obligarlas a abortos o someterlas al robo de sus hijos…

Ingresar al manicomio es ingresar a la mismísima anomia[viii]: no se tuvo vida, la vida comienza y termina en los muros del manicomio.

La falta de ley a la que la palabra anomia refiere es lo que hace del manicomio un territorio que es tierra de nadie… y feudo de unos cuántos a la vez… en ese feudo la crueldad es ejercida con menos sutileza a medida que el ejecutor se aleja de la jerarquía del psiquiatra… y llega al personal de limpieza…

La degradación del concepto de ser humano y ser humano en igualdad de condiciones se traduce en el concepto de enfermo mental que es legislado por una concepción que se rige por un supuesto científico que designa la normalidad de las personas…

¿Quién puede decir yo soy normal, usted es normal y usted no sin sonrojarse?

Solamente alguien enceguecido de soberbia, solamente un ser que tanto teme a la locura, es capaz de pensar que es posible encerrarla tras los muros sin cometer violación de DD.HH.

La anomia en este caso es el estado provocado por un conjunto de personas que han degradado del juramento hipocrático y de otras que ejercen la violación de Derechos Humanos.

Para los que imponen esa legislación –paradójicamente carente de ley- para los que degradan con sus conceptos la condición humana al extremo de la privación involuntaria de la libertad, de tratamientos forzados, de humillaciones, torturas y tratos degradantes… para ellos la concepción de la diversidad funcional no existe y sin embargo, los involucra en tanto seres humanos- lo peor que les puede pasar es probar su propia medicina.

Puedo escribir miles de palabras más para tratar de transmitir la tortura que significa ser privada de la libertad – forma involuntaria o no- y de las graves consecuencias en mi salud y la observada en la salud de otros, como yo, obligados a la ingesta de drogas psiquiátricas en contra de nuestra voluntad.

Sin embargo, los profesionales de la salud mental con compendios de siglas alfanuméricas que definen conductas como los son los DSM y el CIE viven tan pagados de sus saberes y tan pagados por la industria farmacéutica y por los circuitos económicos que se destinan al sistema de salud,

- son incapaces de recapacitar sobre sus prácticas, sobre su negación del paradigma de la discapacidad y ni pensar que puedan asomar su inteligencia al mundo de la diversidad funcional,

- ni pueden comprender un mundo en evolución a velocidades nunca vividas en direcciones impensables hace menos de un cuarto de siglo, que desborda de nuevas problemáticas sociales donde todo parece desquiciado[ix] y estallado -y no necesariamente enfermo- sino nuevo y desconocido.

Como nuevo y desconocido hasta hace poco en Argentina es que nosotros, las PcD psicosocial, tenemos derechos y somos sujetos de derechos, pedimos trato en pie de igualdad y nos negamos a la internación involuntaria y al tratamiento forzado.

Hay una palabra en psicología muy interesante: constructo.

No voy a definir con exactitud el término, voy a explicar que constructo viene a designar esos aspectos que se saben que existen pero son difíciles de probar, de definir o controvertidos al momento de querer hacerlos “objetivables”.

Son constructos la inteligencia, la personalidad y la creatividad.

Me pregunto en qué lugar del cerebro está el recuerdo del olor dulce de mi abuela paterna… y de la voz de mi madre… dónde se guardan las canciones de cuna con las que he mecido el sueño de mis niños… dónde en el cerebro está el registro del primer diente, de la primera risa, de la primera travesura de mis hijos…en qué célula está el clima que rodeaba la escena que recuerdo de mi padre lustrando mis zapatos para ir a la escuela… dónde viven en mí los cuentos de hadas y brujas, el encanto del otoño teñido con el recuerdo del primer beso… donde se localizan los recuerdos de los compañeros desaparecidos, cómo perduran sus voces a pesar de los años… dónde se almacena todo lo aprendido y dónde permanece lo desaprendido, donde se produce y se reproduce la capacidad de amar cuando se ha sido vejada… cómo y donde están objetivados en mi cerebro lo que me permite pensar en colores para pintar, danzar, reír y llorar… olvidar y recordar…

Me pregunto de qué otra manera se puede privar de la libertad en forma involuntaria si no es a la fuerza y si no es desconociendo los derechos que nos atañen.

Esa fuerza tan bien descrita por Antonin Artaud en su CARTA A LOS DIRECTORES DE LOS ASILOS DE LOS LOCOS. “……………………………………………………….No nos sorprende ver hasta qué punto ustedes están por debajo de una tarea para la que sólo hay muy pocos predestinados. Pero nos rebelamos contra el derecho concedido a ciertos hombres – incapacitados o no – de dar por terminadas sus investigaciones en el campo del espíritu con un veredicto de encarcelamiento perpetuo……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ¡Y qué encarcelamiento! Se sabe – nunca se sabrá lo suficiente – que los asilos, lejos de ser “asilos”, son cárceles horrendas donde los recluidos proveen mano de obra gratuita y cómoda, y donde la brutalidad es norma. Y ustedes toleran todo esto. El hospicio de alienados, bajo el amparo de la ciencia y de la justicia, es comparable a los cuarteles, a las cárceles, a los penales…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Esperamos que mañana por la mañana, a la hora de la visita médica, recuerden esto, cuando traten de conversar sin léxico con esos hombres sobre los cuales – reconózcanlo – sólo tienen la superioridad que da la fuerza.[x]

Lucila López

Usuaria y Sobreviviente de la Psiquiatría Psicóloga Social Psicodramatista Analista Institucional Agente Comunitaria en Prevención de adicciones.

Miembro de WNUSP

Miembro de INWWD

C.A.B.A

ARGENTINA

______________________________________________

Escrito por Lucila López en apoyo a la CAMPAÑA POR LA PROHIBICIÓN ABSOLUTA DE LA PRIVACIÓN DE LA LIBERTAD Y EL TRATAMIENTO FORZADO DE LAS PERSONAS CON DISCAPACIDAD PSICOSOCIAL, POR EL CUMPLIMIENTO IRRESTRICTO DEL ART. 14.- Buenos Aires, Argentina, Marzo 14, 2016

[i] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities /Guidelines on article 14 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with DisabilitiesThe right to liberty and security of persons with disabilities/

Adopted during the Committee’s 14th session, held in September 2015

[ii] Estela de Carlotto, Presidenta a Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo uno de los organismos más importantes de Derechos Humanos de la Argentina.

[iii] *) Barrabasada: 2. Hecho equivocado que origina un gran destrozo o perjuicio. (evil thing) RAE

[iv] Y la de todos los privados de la libertad por motivos de discapacidad psicosocial.

[v] Ley NSM viola el art. 12 al decir: “Se presume la capacidad jurídica”… En la CDPD el art. 12 especifica “igual reconocimiento ante la ley”…

[vi] Se hace indispensable el resarcimiento económico.

[vii] *) Para el libre ejercicio del artículo 19, el respeto absoluto del art. 27 – Trabajo y empleo es una condición inalienable y elemental.

Me voy a detener a explicar en el significado de peculio porque es gravísimo que haya muchas PcD psicosocial y con otras discapacidades también, que trabajen con carácter obligatorio y sean pagadas con un peculio porque eso es rayano a un sistema de esclavitud. El Derecho al Trabajo y al Empleo se viola de manera flagrante y es una vergüenza.

Peculio.- Significado – etimología- definiciones. Del lat. peculium.

- m. Dinero y bienes propios de una persona.

- m. Hacienda o caudal que el padre o señor permitía al hijo o siervo para su uso y comercio.

La palabra peculio proviene en su etimología del latín “peculium” que a su vez deriva de “pecus” que significa ganado, ya que esa era la medida que se aplicaba para valorar los bienes, cuando no existía la moneda. Los peculios eran porciones pequeñas de bie

nes, que se separaban en el antiguo Derecho Romano, del patrimonio familiar, que pertenecía en su integridad y en propiedad al pater, jefe de la unidad político religiosa en qué consistía la familia, y varón de mayor edad dentro de ella. Destina una pequeña porción a hijo y esclavos. También relacionado con el ámbito carcelario.

Hasta hace pocos días el peculio era de $150.- mensuales, equivalentes a u$s 0,34 diarios.

Actualmente el peculio es $300.- mensuales equivalente a u$s 20,34 = u$s 0,68 diarios.

Los talleres protegidos para personas con discapacidad están naturalizados y solamente en la Provincia de Buenos Aires, hay 4.500 personas con discapacidad que trabajan en más 173 talleres protegidos. En la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires un importante taller protegido, las personas con discapacidad psicosocial hacen los muebles para la administración pública y hospitales de la ciudad.

El actual valor del peculio en la Provincia de Buenos Aires fue anunciado hace pocos días por el Ministro de Desarrollos Social quien dijo: “van a recibir 300 pesos por mes como parte del peculio, en lugar de los 150 que cobran actualmente, que van a servir no solo para ayudar a ellos sino también a sus familias”. Asimismo informó que los operarios recibirán una tarjeta para la compra de productos alimenticios por un monto de 100 pesos mensuales. (equivalente a u$s 0,21 diarios ¡para alimentos! ¿Y consideran que deben ayudar a la familia!

Al día 14 de enero de 2016 se les adeudaba el pago desde septiembre de 2015.

[viii] Anomia: del gr. ἀνομία anomía.1. f. Ausencia de ley. 2. f. Psicol. y Sociol. Conjunto de situaciones que derivan de la carencia de normas sociales o de su degradación RAE

[ix] Desquiciar

- tr. Desencajar o sacar de quicio algo. Desquiciar una puerta, una ventana.U. t. c. prnl. U. t. en sent. fig.

- tr. Descomponer algo quitándole la firmeza con que se mantenía. U. t. c. prnl.

- tr. Trastornar, descomponer o exasperar a alguien. U. t. c. prnl.

- tr. p. us. Hacer perder a alguien la privanza, o la amistad o valimiento con otrapersona. RAE

[x] http://lalibertaddeotrodecir.blogspot.com.ar/2016/03/carta-los-directores-de-los-asilos-de.html